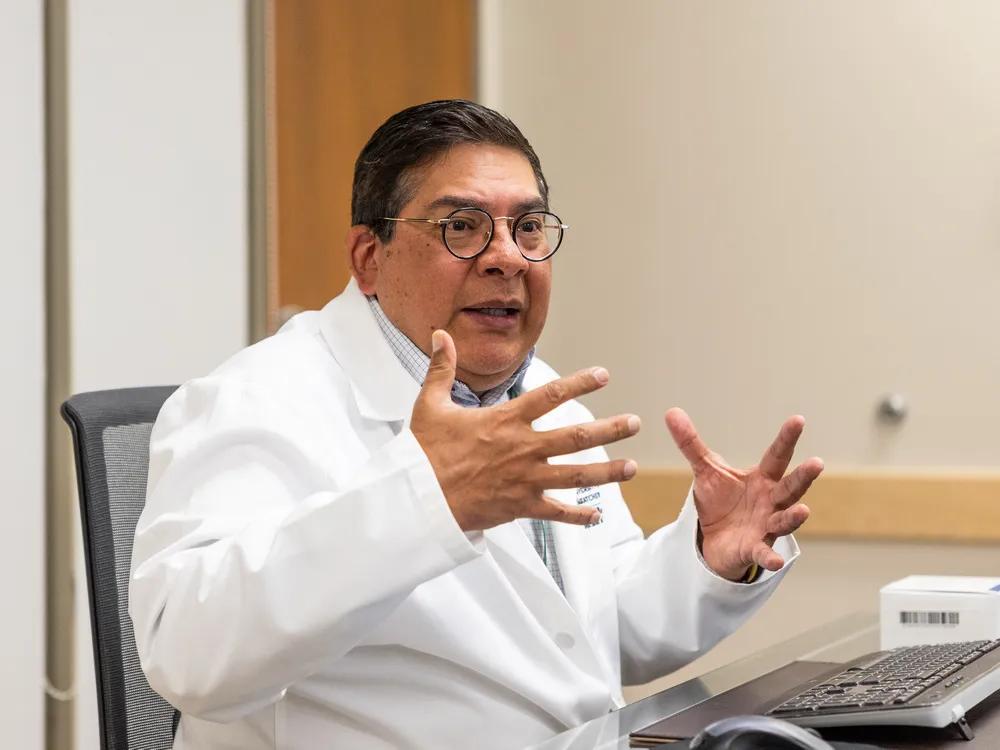

Professional Profile

Dr. Ivar Méndez is a Bolivian born neurosurgeon, Professor of Surgery and innovator in brain repair and virtual health. Based in Saskatoon, he served as the Fred H. Wigmore Professor and Provincial Head of Surgery at the University of Saskatchewan from 2013 to 2022 and now promotes and directs the Virtual Health Hub. His team has developed one of the most advanced virtual medicine and remote presence programs in Canada, leading telerobotic ultrasound and other technologies that bring diagnosis and care to northern and Indigenous communities such as La Loche and Pelican Narrows.

A reference in functional neurosurgery and neuromodulation, he has researched cell transplantation for Parkinson’s disease and other approaches to brain repair. His clinical and academic training includes a BSc from the University of Toronto, an MD and PhD from Western University, and fellowships with the Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons of Canada and the American College of Surgeons, with board certification in neurosurgery.

Beyond the operating room, he founded the Ivar Méndez International Foundation, which promotes nutrition, health and education for girls and boys in remote communities in the Bolivian Andes, with a special emphasis on creativity and access to art. In 2022, he was appointed an Officer of the Order of Canada. His work integrates high technology and social justice, aiming to deliver quality health care to rural and remote populations while honoring the cultural and social context of each patient.

April in Ottawa. A clear sky that deceives and an air that cuts the skin. As a newly arrived teenager from Bolivia, Ivar Méndez hears someone exclaim, “What a beautiful day.” The sun is real, but so is the cold that numbs his hands. He cannot reconcile how “cold” and “beautiful” can coexist in the same sentence. Decades later, he would learn to read that code. Beauty does not cancel harshness; it accompanies it. In that opening scene between light and frost, there is already space for the two lines that would define his public life: clinical rigor that refuses to ignore human context, and a practical optimism that prefers to open paths rather than lament borders.

His story matters in both Canadian and Latin American frames because of its unique crossroads. He is a doctor and scientist who studies and treats the brain, and an artist and philanthropist who builds cultural and social tools. He is an immigrant who embraces the opportunities of Canada and maintains an intellectual and emotional umbilical cord with Bolivia. Méndez describes that triad of science, art and philanthropy as “synergistic.” These are not separate compartments, but communicating vessels. The same focus that guides a neuromodulation procedure in the human brain informs a sculpture or photograph. The same sensitivity that attends to a child’s drawing in a Bolivian village shapes a telemedicine program for a remote northern community.

Born in La Paz, he immigrated to Canada as a teenager with his family. “I am Bolivian,” he says without hesitation, and at the same time “Canadian by trade and destiny.” In Canada he built a career as a neurosurgeon and scientist with a deep interest in technology and the human brain. The other half of his biography beats outside the operating room. He sculpts, takes photographs and has published several books. For Méndez, this is not a series of hobbies, but part of a broad understanding of what it means to be human. The brain does not simply coordinate bodily functions; it imagines, remembers and creates. Artistic practice is not the opposite of science; it is one of the ways science listens to the human condition.

From Bolivia, he does not remember only landscapes. He remembers seeing poverty up close and learning that “a patient is not just a disease, but a human being with culture and socioeconomic context.” That apparently simple phrase condenses a method. In his view, Latin American experience does not end in warm gestures or familiar food. It provides clinical criteria. A diagnosis that ignores the patient’s biography is incomplete from the start. “Being Latino allowed me to develop empathy and a global perspective,” he explains. That empathy became practice both in Canada and in Bolivia.

His first years in Canada were, in his recollection, demanding but hopeful. He did not experience constant, overt discrimination and insists that Canada “offers real opportunities” for those who work with perseverance. That first snapshot of an icy and bright day eventually became a reading of the country itself: a demanding environment where it is possible to set ambitious goals and, with discipline and institutional support, reach them. The comment is not a slogan but a summary of lived sequences of study, training and service.

On the scientific side, his career moved early toward the intersection of biology and technology. “From a young age I was fascinated by the brain,” he recalls. Specialization came through functional neurosurgery and neuromodulation, including the placement of electrodes in the brain to treat conditions such as Parkinson’s disease and depression that does not respond to other therapies. This work belongs to what is now known as brain machine interface, points of contact between neural circuits and devices capable of reading or modulating their activity. Yet technical fascination was never detached from an ethical question: what is the point of exploring the limits of this interface if those advances never reach the people who need them most?

From that question grew another axis of his work: applying artificial intelligence, robotics and telemedicine so that care can travel where geography and history have conspired against access. In Canada, he emphasizes, these technologies have especially benefited Indigenous communities in remote areas, where distance and weather can turn treatable problems into fatal outcomes. In his account, virtual care is not a futuristic promise but a set of concrete bridges. A telerobotic ultrasound unit that allows a specialist in Saskatoon to examine a patient hundreds of kilometers away, a secure link that connects nurses in La Loche or Pelican Narrows to a surgical team, an algorithm that helps triage scarce resources: for Méndez, these are different pieces in the same design for equity.

Philanthropy followed a similar logic. Méndez founded a Canadian organization that works with remote communities in Bolivia, with a focus on children. The emphasis is not simple charity. The foundation provides nutrition, basic health care and, crucially, opportunities to explore creativity through art. It is a deliberate list. The urgent needs are met without forgetting what builds the future. His conviction is that “real change comes from within communities and starts with children.” Creativity, in that equation, is not decoration. It is a language to name the world and to imagine another kind of belonging.

Latino identity, far from being a constraint in his scientific career, is in his words “an attribute that enhances everything I do.” The key word is “holistic.” More than a style, it is a prism for seeing the whole picture. Growing up in a country with visible inequalities reminds him again and again that a single technical intervention can have very different impacts depending on place, culture, income and trust between patient and system. That awareness, he argues, improves both the clinical quality and the social legitimacy of medicine.

His advice to young Latinos who come to Canada moves in two clear directions. First, never deny your origin. Your culture is personal wealth and a public contribution. Erasing that anchor impoverishes imagination and narrows the margin for innovation. Second, persevere. Not as a vague slogan, but as a concrete discipline: set goals, work consistently and accept that long journeys often yield more than instant shortcuts. “Canada is a country where, with effort, goals are achievable,” he says. “Everything I set out to do, with discipline and with the support of the Canadian environment, I have achieved.”

In his vision of the future for the Latino community in Canada, the central verb is “to unite.” Méndez invites people to recognize themselves as a single community that goes beyond national borders. This is not a call for sameness but for strategy. Internal diversity of accents, histories and professions can be a strength if it is organized. Science, innovation, politics, art and business are all spaces where Latinos already work and where, if they consolidate a sense of collective identity and act as an engine of change, their contribution can become more visible and decisive. In practice, unity means mentoring networks, shared research projects, cultural platforms with rigorous programming and a stronger presence at decision making tables.

His biography allows us to identify clear achievements. He has built a career in neurosurgery and research with a focus on neuromodulation, including the placement of electrodes to treat Parkinson’s disease and treatment resistant depression. He has pursued brain machine interface research and implemented telemedicine programs that benefit Indigenous communities in remote parts of Canada. He has continued his artistic practice in sculpture and photography, published books, and founded a Canadian organization devoted to nutrition, health and art programs for children in remote Bolivian communities. The details come from his own account, without an exhaustive list of dates or institutions, but they trace a coherent map.

The closing inevitably returns to that April morning. The teenager who could not understand how cold could be called “beautiful” became a professional who learned to read the ambivalence of his environment. Canada demanded that he train hard in a competitive system and, at the same time, offered real opportunities to translate that training into impact. What changed was not the weather. It was his way of seeing. The cold ceased to be only an obstacle and the sun ceased to be only comfort. In the phrase he repeats to those who come after him, “never deny your origin; persevere,” you can hear an echo of that learning. Humanizing medicine, using technology to take it further and returning again and again to childhood as a territory of the future: for Dr. Ivar Méndez, that is how you help balance the scales.