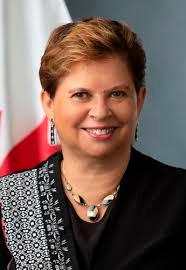

Professional Profile

H.E. Lilly Nicholls is a Canadian diplomat of Chilean origin whose career spans more than three decades of international development and foreign service. She served as Ambassador of Canada to Panama from 2018 to 2021 and as High Commissioner of Canada to Bangladesh from 2022 to 2024, representing Canada in two key regions for human rights, climate resilience, and inclusive growth.

At Global Affairs Canada, Nicholls led the research team that supported the Feminist International Assistance Policy, helping to anchor Canadian cooperation in evidence and a gender equality lens. Her work has connected public institutions with the UN system, academia, and civil society, with a focus on governance, poverty reduction, and inclusive partnerships.

Today she continues to contribute as an analyst and visiting academic, promoting female leadership and evidence based public policy. Her trajectory and her appointments in South Asia make visible the contribution of the Latin American community to Canadian foreign policy, integrating diplomacy, research, and advocacy.

The foundational scene of this story unfolds at a distance. In Santiago, a military coup topples a government. In Ottawa, a Chilean doctor and health adviser to President Salvador Allende attends a conference and receives a warning that freezes him: if he returns, he will be arrested at the airport. It is 1974. His daughter, Lilly Nicholls, is ten years old. A few days later, the family lands in Canada in January, with no familiar language and no sense of season, carrying the raw feeling of having left their house half closed. “We were exiles, not voluntary immigrants,” she recalls. The difference, she insists, is not semantic. It describes a particular kind of loss and a particular kind of impulse.

Her story shows how a biography marked by expulsion can become, through work and method, a trajectory of foreign service that keeps the memory of exile as an ethical compass. It matters because it offers a clear eyed reading of the host country: the less diverse Canada of the 1970s and the Canada of today that, with all its debts, made it possible for a Chilean Canadian girl to officially represent her new home without renouncing her roots.

The origins explain much. Her father was a doctor and health adviser in the Allende government. Her mother taught at the University of Chile’s Faculty of Social Work. Both were committed, she says, to social programs and innovative poverty reduction policies. The house breathed public deliberation. Policy was a topic at the dinner table; solutions and rights were discussed as daily subjects. That intellectual climate became both legacy and mandate.

In Canada, with few networks and an environment that was “much less diverse than today,” the family chose a path: education as the main tool for advancement and meaning. A key fact in that choice was that neither of her parents had their professional qualifications recognized when they arrived. With four young children and belongings left behind, only one of them could retrain. Her mother sacrificed her career and never worked again as a professional social worker in Canada. Her father repeated much of his training and worked as a medical researcher at Health Canada, but did not recover his full specialty as an epidemiologist and public health expert. “My parents always insisted on education,” Nicholls says. From that emphasis came her first professional door: the then Canadian International Development Agency, CIDA.

The arrival was not a romantic adventure. It meant learning to live with no language, an unfamiliar winter, and a constant feeling of loss. In the case of exile, she adds, the experience is traumatic because of abrupt uprooting, the anguish of forced displacement, and a lingering concern for family and friends left behind. One lives permanently reconciling past, present, and future, and trying to hold attachments to both the country of origin and the host country, without fully fitting in either. Exile, she warns, is a practical category. The urgency is not to integrate out of courtesy, but to rebuild life.

That realism did not cancel vocation. It powered it. Influenced by Latin American experiences of dictatorship, poverty, and human rights struggles, she oriented her interests toward social policy and international cooperation that could improve daily life. From a young age, she was involved in protests, lobbying, and projects that sought to promote democracy and human rights in the region, working from her new Canadian home.

The path she followed has a recognizable thread: to learn, to represent, and to connect. The first verb refers to her long career in development and cooperation, with CIDA as her early school and platform. The second speaks to the diplomatic roles she would later hold as ambassador to Panama and High Commissioner to Bangladesh. The third points to her way of exercising those functions. “Being a Canadian ambassador to a Latin American country was a great honor,” she says. Her Chilean Canadian identity was not an ornament on a lapel. It allowed her to get closer to communities, understand local realities, and build bridges with other ambassadors and with citizens. Representing Canada “with my Latin roots,” she says, was a dream come true.

Double belonging does not stay at the level of biography. It shapes a style. When Nicholls speaks of a “diverse and holistic vision,” the phrase is not a slogan. It comes from a clinical and social method inherited from home: a patient, or a country, is not just a set of indicators. It is a human being with culture and socioeconomic context. That approach, rooted in Latin American public health and social work, underpins her leadership in Canada. Empathy, in her practice, does not sugarcoat problems. It cuts them more precisely. It helps her read layers of culture, class, and history that determine whether a policy will succeed or fail.

The same logic runs through her work on gender equality. Nicholls participated, by her own account, in the development of Canada’s feminist foreign policy and made one of her priorities the implementation of that policy in Latin America. She cites a concrete example from her time in Panama, where she organized a regional gender course for Central America and the Caribbean under Canadian leadership, aimed at government officials. In parallel, she helped promote courses on gender and planning for women in politics through PARLAMERICAS and the National Forum of Women in Political Parties, FONAMUPP. This meant more than adding new language to traditional programs. It meant inserting strategic questions about who decides, who has access, and who does unpaid care work into the design and evaluation of projects.

Early exile also leaves productive scars. Nicholls has asked herself many times what her Latin American heritage means in practice. She doubts, reflects, and returns to one point. That heritage gave her codes of closeness that made her roles of representation more porous. In corridors and neighborhoods, where diplomacy learns its grammar beyond protocol, Latin roots sharpen listening and open doors. Canadian identity, for its part, brings institutional credibility, method, and continuity. Diplomacy works best, she suggests, when those two layers do not compete but reinforce each other.

The path is not traveled alone. “I am part of a network of Latin diplomats,” she notes, emphasizing the work of accompanying young people who want to devote themselves to public or international service. Her advice is pragmatic. “Do not stop,” she repeats to those who hear that, because they are Latinos, they will never represent Canada. She breaks down her recipe: education as the key to opening doors, Latino identity as a differential value that enriches rather than subtracts, and a reminder of responsibility. As diplomats and public servants, she stresses, “we represent Canada.”

Her reading of the future for the Latino community in Canada is both memory and bet. Memory first. “In the past, our communities were very divided for political reasons and that weakened us,” she says. The bet comes next. The present shows collaboration between embassies, film and literature festivals, and greater visibility of Latino politicians and leaders. The challenge, she insists, is to overcome old divisions and work together to showcase contributions in culture, politics, and entrepreneurship. The goal is not uniformity but coordination. A choir does not require identical voices. It requires a shared score.

The verifiable achievements mentioned in her account trace a precise map. She arrived in Canada in January 1974 as an exile. She entered CIDA and oriented her career toward human rights and development. She contributed to the formulation of Canada’s feminist foreign policy. She served as ambassador to Panama and High Commissioner to Bangladesh. She helped organize a regional gender course for Central America and the Caribbean, targeted at government officials, and courses for women in politics through PARLAMERICAS and FONAMUPP. She has also invested time in Latin American diplomatic networks that mentor new generations and make community achievements visible.

Alongside those milestones are less visible but decisive elements: doubts, adjustments, discipline. Nicholls remembers a Canada that was “much less diverse,” where learning meant becoming concise in certain forums without erasing warmth, keeping her roots in sight without mistaking them for obstacles, and channeling the sense of loss left by exile into a practice that honors it by opening spaces for others. If one idea sums up her journey, it is that multiple belonging can be a comparative advantage. For her, being Chilean Canadian is not a decorative detail for occasional speeches. It is an operational tool for negotiating, explaining, and building.

In the end, the story returns to the ten year old girl crossing a foreign winter. Fifty years after that January, the phrase Nicholls addresses to a young Latina who arrives in Canada with big dreams sounds less like advice and more like a transfer of practice: “Do not stop. Study. Use your identity as a value. And remember who you represent.” The formula seems simple. The work behind it is not. Yet her history, made up of classrooms, institutional corridors, protest marches, and negotiation rooms, suggests that the sum works. In the biography of H.E. Lilly Nicholls, exile did not remain a footnote. It became, methodically, a starting point.